We only recommend products that we use and believe in. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

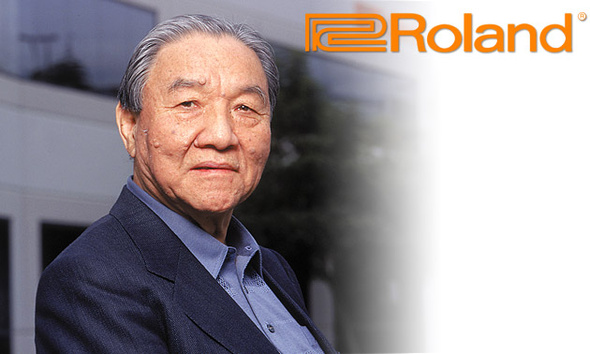

Roland Corporation Founder, Co-Founder Of MIDI Dead at 87

From Music Trades Magazine

IKUTARO KAKEHASHI, an electronic music industry pioneer who over a seven-decade career co-authored the MIDI standard and founded Roland Corporation, died on March 31. He was 87 years old. At the time of his death, he was chairman of ATV, a new electronics company he founded three years ago. Born in Osaka, Japan in 1930, Kakehashi was an entirely self-taught engineer who overcame extraordinary hardships to build a billion dollar enterprise.

Kakehashi was orphaned at age two, when his parents succumbed to tuberculosis, and placed in the care of his grandparents. As a schoolboy, he worked in the Hitachi shipyards in Osaka, where Japanese “midget” suicide submarines were being built, and witnessed up-close the destruction of WWII. In 1946, due to acute food shortages in Osaka, he moved to Japan’s southern Island of Kyushu, where he secured farm work and was paid in rice. At 16, he opened a watch repair business. No new timepieces were available, so despite his inexperience there was a tremendous demand for his repair services. He later recalled, “I learned watchmaking at my customer’s expense. Actually, a lot of them were really my victims, not customers.”

After four years in Kyushu, he had saved enough to enter Osaka University, but his plans were derailed when he was struck down by tuberculosis. He spent the next two years recovering in the Sengokuso hospital, where he read extensively and supported himself by repairing watches and later radios. It was through listening to the radio that he developed an intense interest in music and began tinkering with crude musical devices.

Upon leaving the hospital, he opened a radio shop in Osaka, and at night he began work designing an electronic organ. But with keyboards and tabs unavailable, he shifted his efforts toward the lesser challenge of building rhythm units. On the strength of several working prototypes, in 1958 he launched Ace Electronics and one year later shored up the company with an equity investment from Sakata Shokai, a manufacturer of printing ink.

In an era that predated “venture capital,” Kakehashi’s Ace Electronics didn’t have the luxury of a lengthy incubation period. Funds were so tight that the company faced two alternatives: become self-sustaining quickly, or perish. This unforgiving environment had a lasting impact on Kakehashi’s approach to R&D. “No one can afford to waste time or money, and you have to learn to admit your mistakes in a hurry and move on,” he later explained.

Kakehashi founded Roland Corporation in 1972.

Despite some initial protests from the American Federation of Musicians, who worried that electronic rhythm machines would put musicians out of work, the Ace Electronic product line found a ready market in the U.S. and Europe. In addition, the company did a thriving business selling rhythm machines to Kimball and Hammond Organ. Hammond management quickly recognized Kakehashi’s talents and in 1968 tapped him to head Nihon Hammond, a joint venture between the organ maker and Ace Electronics. Initially, Nihon Hammond distributed Hammond products in Japan, but it gradually began to participate in research and development and product design. In 1969 the Japanese organization, under the direction of Kakehashi, played a key role in the creation of the Piper, Hammond’s groundbreaking entry-level, single-manual, easy-play organ. The first three prototype units were handmade by Kakehashi’s team and air freighted to Chicago. The project was so secret and well managed that Kakehashi didn’t even know the final name “Piper” until after its Miami debut in 1970. The project was code named “Mustang.”

In a short period of time a series of unexpected events quickly soured the prospects of Ace Electronics and Nihon Hammond. First, Sakata Shokai fell on hard times and was taken over by Sumitomo Chemical. The giant company had no interest in a music subsidiary and promptly tried to pry surplus dividends from Ace Electronics. Shortly thereafter, Hammond abandoned its tone-wheel technology in favor of a new LSI system that Kakehashi categorically declared “would not work” because, at that time, MOS LSI were very sensitive to static electricity. Faced with an intractable corporate parent and a poorly managed partner, he resigned from Ace Electronics and Nihon Hammond. Subsequent events vindicated his judgment. Ace Electronics failed shortly after his departure, and Hammond’s LSI organs were a monumental disaster that led to the company’s long downward slide.

In 1972, after walking away from Nihon Hammond, Kakehashi and a team of six launched Roland in a small garage in Osaka with financial backing from the founders of consumer electronics giant Pioneer Electronic Corporation. However, after his previous experience with unreliable partners, Kakehashi maintained an effective majority on the board of directors. For initial products, he opted to build two different rhythm machines and a guitar amplifier because, as he later said, “we could get them into the market quickly and lay a foundation of products for the business.”

Like most startups, the fledgling organization lacked capital and operated on a shoestring budget. Yet these material limitations were more than offset by Kakehashi’s long-term vision for harnessing electronic technology to create products that would thrill musicians and audiences alike. From the earliest planning stages, he harbored global ambitions for his upstart company and wanted a memorable trade name that was easy to pronounce in languages around the world. Combing through an English phone book, he enthusiastically latched onto the name Roland and promptly trademarked it. Back home, however, the new name created an unexpected problem. There is no “L” sound in the Japanese language, so none of the employees at Kakehashi’s new venture could properly pronounce the company name.

The problems employees had pronouncing the name had no adverse impact on the company’s performance. Roland made a profit in its first full year of operation and saw nearly three decades of double-digit sales growth, fueled by a succession of innovative products. With the CR-78 in 1978, the company created the first fully programmable rhythm machine; the Roland EP-30, unveiled in 1974, was the first electronic piano with a touch-sensitive keyboard; the JC-120 Jazz Chorus amplifier was the first guitar amp to feature onboard signal processing; with the MC-8 in 1977, Roland created the first digital sequencer. Other Roland breakthroughs included pioneering the MIDI standard, creating the standard MIDI interface (MPU-401) for linking musical instruments with PCs, developing the guitar synthesizer, and the VS-880, the first practical, affordable, hard-disk recording system.

In 1973, Kakehashi addressed the guitar market with a line of effects products under the “MEG” (Musical Electronics Group) brand name. A year later, after U.S. dealers told him that guitarists wouldn’t buy a pedal named after a girl, he adopted the Boss trademark. He later said that the Boss line got an enormous boost at the 1977 NAMM show thanks to the unintentional endorsement of an artist who was demonstrating a new Gibson Lab series guitar amplifier. When dealers asked why the amp sounded so good, the artist pointed to a Boss effects pedal. The artist was fired the next day, but Boss left the show with a bulging order book.

In the late ’80s, after the spectacular collapse of the electronic drum market, Kakehashi oversaw the introduction of a new line of electronic drums. Competitors scoffed, but he reasoned that drummers would respond to the idea of an easy-to-record kit that could be played with headphones. Today, Roland’s electronic drums consistently rank among the company’s top ten selling products.

In 1981, Kakehashi entered the computer business with the launch Roland DG. The initial motivation for the new venture was to secure better pricing on component parts. After introducing a line of modestly successful computer monitors and peripherals, the Roland DG found a niche producing specialized sign printing equipment. Now independent of the Roland musical instrument business, Roland DG had revenues of $400 million last year.

In commerce, there are inspiring salesmen, visionary engineers, and shrewd dealmakers. Kakehashi was the rare individual who combined an equal measure of all three talents. His sales skills were reflected in the unique international distribution model he structured. Rather than just assign product lines to existing distributors, he enlisted skilled local talent to create 50/50 joint venture distribution companies, half owned by Roland, half owned by a local manager. The 50/50 ventures helped the start-up rapidly gain a global presence with limited capital expenditures. Kakehashi also said the idea was inspired by his experience growing rice on his uncle’s farm in the years after World War II. “I was always tired, and I couldn’t understand why my uncle was never tired. Then I realized that he worked so hard because it was his farm.”

While listening to the radio in post-war Japan, Kakehashi developed a lifelong passion for the organ. This enthusiasm led to one of the few missteps in his storied career. In 1988, he acquired Rodgers Instruments, a leading maker of church organs. Two years later, he introduced the Roland Atelier line of home organs, convinced that innovative new products would revive the market. Despite major marketing outlays, both Rodgers and the Atelier line were financial drains on the company.

Kakehashi continued to exert managerial control at Roland even after mandatory retirement requirements had forced him to resign as CEO and step down from the board. Four years ago, after sharp disagreements on strategy with the board, he severed all ties with the company and sold all his Roland shares. Still committed to advancing electronic music, he went on to launch ATV with a line of percussion and video products. When asked about the new company, he explained, “People will probably say that it’s a foolhardy undertaking considering the physical difficulties that come with age, and they’re not all wrong. But the work we do with electronic musical instruments will not end with my generation. One of my missions is to foster the next generation of talent to carry on the work. From that perspective, it’s only natural that I continue to work one day at a time to fulfill this mission.

Kakehashi is survived by his wife of 66 years, Masaka, and three children.